Writing a WebSocket Client

I recently tried my hand at writing a WebSocket client. Some background as to why an individual would spend their weekend reinventing a wheel reinvented thousands of times over, was that I was working with WebSockets in Java and found most of the existing solutions to be annoying for very particular reasons.

I’ve been designing a low-latency trading engine in Java and most of these existing WebSocket solutions generated a fair amount of garbage, leading to costly GCs. For an intuitive reader, that sentence may raise some immediate concerns:

Intuitive reader: “Hey Mason, why would you be using WebSockets for a trading engine?”

Unfortunately, I cannot afford data fees for US exchanges. And a further unfortunate-ness, SIP data is too slow to ever practically compete in the HFT space (even the HFT-retail space I like to say). This leaves me with a limited amount of options: crypto HFT. Crypto exchanges predominantly function on WebSockets – I’ll write no more on this.

Intuitive (and now skeptical) reader: “Alright Mason, another question for you, why do you care about GC time?”

That’s a good question, reader, and the answer to that is I probably shouldn’t. A large GC cycle can take on the order of a few milliseconds, which, when compared against things like network speeds to even get to a crypto exchange, these milliseconds may be negligible to the jitter on the network call alone. One may call this a premature optimization, and I may agree with that one person. However, I’ve been enjoying writing a trading engine from scratch and desire to see just how low latency a retail trader may get.

Intuitive reader (if they’re still here): “Sure, Mason. Anyways, why Java? If you are setting a goal for minimizing latency on all possible avenues, why not C++? It’s faster in most cases.”

Another great question, reader. The main reason comes from the fact that I am more experienced in Java and do not have a desire to increase my C++ depth currently. I’ve used C++ for a number of projects and enjoy the language, but Java is where I’m most comfortable. Further, JIT and the JVM have come a long way. Using one of Azul’s limited GC JVM’s can get comparative performance to C++ out of the box.

General WebSocket thoughts

Reading the RFC 6455’s proposal to understand WebSockets was a wild ride. First, who calls themselves the Internet Engineering Task Force? I feel like I need to put gun emojis at the end of that name. Needless to say, I went into the document already extremely intimidated.

The document was surprisingly easy to parse. Any time I open up a manual-looking document on the internet, I immediately feel like brain-glossing gets activated. However, this one was pretty consumable. Nearly all the document I was aligned with the suggestions, besides the evil fragmentation. It seems like a great idea in a proposal, but let me tell you, trying to implement fragmentation sends your code quality into the dumpster. A WebSocket client can practically be stateless (other than the connection on the wire) unless you need to implement fragmentation. All of a sudden, one needs to save the entire last message received into an internal state and wait for the subsequent messages to be fully parsed and understood before the frame is complete. To make matters worse, frames can be interlaced between fragmented messages so you don’t even have the guarantee the next frame received will finish the fragment. If you could not tell, I skipped over implementing fragmentation.

Design goals

Here are some high level goals I kept in mind while writing the code. No, I did not initially lay out the code design, I just dove right in like any good developer.

Comparative speed to C++/boost

I struggled with the C++ or Java choice for a while before ending up on Java alone. I had an internal battle to prove that my choice was not completely unfounded.

Reader-initialized polling

Most WebSocket clients take a hands-off approach to designing the contracts between the programmer and the client. The client does all the heavy lifting, and the programmer only needs to worry about when a message is received. Sweet deal for the programmer as long as latency is not on their radar. Usually this heavy lifting is done by spawning reading/writing threads to poll/write on the wire away from the main thread. However, IPC ain’t free. My use case for a WebSocket client is predominantly a single thread, pinned to a core, reading from a wire and immediately writing the data elsewhere. This bodes well for having the programmer take responsibility for polling the wire if any message is waiting for us.

Read-first-write-never

All of these crypto exchanges handle data intake via REST rather than writing over WebSockets. This effectively leads to us never needing to write on the WebSocket besides on first connection. Approaching writes from the perspective of existing WebSocket clients (background writer threads) creates an easy path for us.

Memory management

At a high level, data flow on the hot path looks as follows:

Bytes -> [NIC -> Kernel -> User Space] -> Socket Recv Buffer -> User -> [Anything]

The only data truly necessary in the hotpath is a view into the socket receive buffer. This buffer can be interpreted by the WebSocket client to determine what kind of frame was sent and easily send it off to the user without any modification (as long as we trust this user). Ideally this buffer is small enough to fit entirely into an L1 cache (32kb) and not clobber the entire thing (<32kb). I chose 16kb after some experimentation, and it seems to be a good size. Cache alignment is important here as well.

Kernel bypassing and copying bytes

In the code block above, the section surrounded by [] represents where the bytes flow without Kernel bypassing. With Kernel bypassing, it may look something like:

Bytes -> NIC -> Socket recv buffer -> User -> [Anything]

This can avoid copying the bytes from the Kernel into userspace and then back into the location of the application’s recv buffer (probably the heap). Instead, if this recv buffer lives in some memory mapped area, and we are running some sort of Kernel bypass software (DPDK…), the NIC can write directly to our buffer in user space.

Most of this idea does not involve the WebSocket client directly. All that is necessary for the client design is to not force any strict requirements onto the Socket and use some sort of socket facade that you can plug a Kernel-bypass-capable socket into.

Automatic reconnection

Because crypto is crypto, frequently a connection via WebSockets to an exchange will get dropped or quietly stop sending messages. The WebSocket client should be intelligent enough to recognize that no bytes have been received on the wire after X amount of time and try to reconnect itself. This can be monitored in a background thread to not flood the hot path.

Results

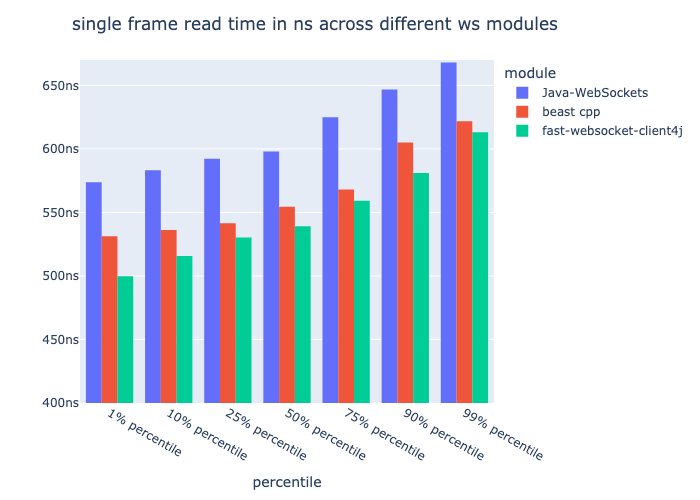

Here’s a Plotly graph I threw together. I have not taken the two hours required to learn Excel plotting yet in my life.

The code that generates these numbers is here. The numbers came from the total time to read 1,000,000 sequential numbers from a WebSocket server in a TCP loopback. This number is then extrapolated to a (very) rough estimate of the time to parse a single message from the wire. Well, we beat boost, where’s the champagne?!

Eh, not really. We have an extremely targeted use case which we also only tested this one niche benchmark. However, this use case is all I have plans for with WebSockets (if everything in my life goes to plan that is, I don’t want to touch these anymore), so I’ll claim to have won anyway. Just don’t test fragmentation, writing, proper closing frames, maybe a few other things, and I’ll still claim victory.

On Microbenchmarking

The benchmark code is pretty rough. In an ideal scenario, we use something like JMH or JLBH, but then that would require a similar framework in C++ since we’re testing cross-language, and that sounded like too much work for what it was worth.

Source code

The client is open-source. Please feel free to read through it and criticize any part your heart desires.